A History of PA’s Megan’s Law and the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA).

Part 2

By Randall – July 29, 2021

As we saw in Part I, litigation challenging Pennsylvania’s Megan’s Law began shortly after it’s enactment in April 1996 and reached the Supreme Court of PA (SCOPA) in 1999.

Megan’s Law II

Following the SCOPA Williams decision in June 1999, the PA Senate introduced legislation that remedied the flaws with Megan’s Law. Following several amendments and passage in both the Senate and House, “Megan’s Law II” (ML II) was signed into law by Governor Ridge on May 10, 2000.

Two significant changes were made to PA’s sex offense registration scheme. First, the burden of proof that a person was a “Sexually Violent Predator” (SVP) was now on the State, rather than on the offender: the Commonwealth had to provide clear and convincing evidence that a person deserved to be labeled an SVP. The other significant difference in ML II was that a person labeled an SVP was no longer subject to an automatic increased maximum sentence of life in prison. ML II also created serious legal consequences for failure to register.

On September 25, 2003, the Supreme Court of PA found that portions of Megan’s Law II were unconstitutional in Com. v. Gomer Williams (Williams II):

“In the absence of competent and credible evidence undermining the relevant legislative findings, Megan’s Law’s registration, notification, and counseling provisions constitute non-punitive, regulatory measures supporting a legitimate governmental purpose. Therefore, these measures are presently upheld against Appellees’ claim that they result in additional criminal punishment. The prescribed penalties for failure to register and verify one’s residence as required are unconstitutionally punitive, but severable. Accordingly, those provisions are invalidated, and the matter is remanded to the trial court for consideration of Appellees’ remaining constitutional challenges.”

Here, the Court affirms that registration furthers the interest of public safety and that being on Megan’s Law is not punishment.

However, the court finds that penalties for failure to register are punishment and should be removed from the law. This is because judicial findings that result in punishment beyond what is on the books as a penalty for a crime must be submitted to a jury and proven beyond a reasonable doubt. As mentioned above, SVP status was determined by a less rigorous standard: clear and convincing evidence.

The PA Supreme Court ruled that these penalties / punishments had to be severed (removed) from the law. Importantly, however, the registration, notification, and counseling requirements of ML II were determined to be regulatory, and therefore non-punitive and constitutionally sound.

Megan’s Law III

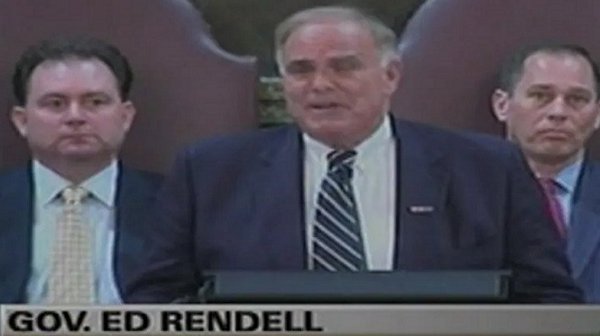

In response to this Supreme Court decision, the General Assembly of PA once again drafted and passed legislation to fix the problems with the registry. Governor Rendell signed Act 152 of 2004, also known as Megan’s Law III (ML III), into law on November 24, 2004.

This third iteration of a public sex offense registry was only part of 40+ page piece of legislation that had many facets. As far as sex offenses, ML III:

-

- Broadened the penalties for people who fail to register

- Added more crimes to the list of offenses which require registration

- Directed the PA State Police (PSP) to create a searchable online database of people with sex offenses

- Allowed lifetime registrants to petition for removal from registry after 20 years

- Established community notification for people labeled SVPs

- Required fingerprints and photographs when registering.

ML III required that people convicted of sexual crimes report the following information to the PA State Police:

-

-

- Residence

- Employment

- Enrollment in a learning institution

- Changes to any of the above items

-

There were several elements of Act 152 that did not affect sex offense policy:

-

- Established a 2-year window for asbestos-related legal actions

- Amended court procedures after the execution sale of real property

- Amended how landlord-tenant evictions may proceed

- Changed how county park police are created in third-class counties.

ML III enjoyed stability for much longer than previous laws governing how sex offenses are handled. It wasn’t until 2011 that major changes came to PA’s registry, and this time not as a response to litigation.

In 2006, the US Congress and President G W Bush passed the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act, also known as the Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA). This federal law increased penalties for federal sex crimes (including mandatory minimums), created a national DNA database for people convicted of sex offenses, and established guidelines for civil commitment of federal prisoners.

On the state level, the Adam Walsh Act (AWA) sought to create a standardized system of sex offense registries in all US states and territories. This system used 3 Tiers which categorized registrants based on the offense they were convicted of. While the law did not require that states use the AWA registry scheme, a penalty could be imposed if a state did not comply: a 10% loss of federal Byrne Justice Assistance Grant funds each year. (In PA, this 10% loss is currently approximately $650,000. See our article here.)

SORNA

Inspired by the AWA, the Pennsylvania General Assembly drafted a version of SORNA in 2011. Governor Corbett signed the bill on December 20, 2011 and the law went into effect one year later, on Dec. 20, 2012.

(The enactment of SORNA replaced the registration requirements of ML III, but legal challenges against ML III had been underway for years. In the case of Commonwealth v. Neiman, decided on Dec. 16, 2013, SCOPA ruled that ML III violated the single-subject rule of the PA Constitution:

“No bill shall be passed containing more than one subject, which shall be clearly expressed in its title, except a general appropriation bill or a bill codifying or compiling the law or a part thereof.”

As described above, ML III / Act 152 addressed a wide range of maters that could not be considered germane to one subject. While ML III was not found to violate civil liberties or criminal procedure, the ruling showed a degree of carelessness by the General Assembly when it came to passing laws affecting sexual offenses. Because PA’s 4th registration scheme was already on the books by the time of Neiman, however, this decision was largely moot.)

SORNA in PA was made law in order to comply with federal SORNA guidelines, to require people with sex offenses to register, to provide for a means for the public to access and search an online database of people convicted of sexual offenses, and to streamline information sharing among state and federal police agencies.

The legislative findings and statement of policy that introduce the text of SORNA lay out the rationale for the implementation of this law. Among them:

(3) If the public is provided adequate notice and information about sexual offenders, the community can develop constructive plans to prepare for the presence of sexual offenders in the community. This allows communities to meet with law enforcement to prepare and obtain information about the rights and responsibilities of the community and to provide education and counseling to residents, particularly children.

(4) Sexual offenders pose a high risk of committing additional sexual offenses and protection of the public from this type of offender is a paramount governmental interest.

(5) Sexual offenders have a reduced expectation of privacy because of the public’s interest in public safety and in the effective operation of government.

(6) Release of information about sexual offenders to public agencies and the general public will further the governmental interests of public safety and public scrutiny of the criminal and mental health systems so long as the information released is rationally related to the furtherance of those goals.

In 2014, a defendant named Jose Muniz appealed the portion of his sentence which required him to register for life under the provisions of SORNA. This was the first step in a process that would once again bring PA’s sex offense laws under scrutiny by our highest court.

The SCOPA Muniz decision, which we will examine in Part 3, would result in a massive change in how PA handles registration of those convicted of sex crimes. It is the basis for the confusing and vastly different concurrent registration schemes that we have in place today.

For a sneak preview of these schemes, have a look at our “What you need to know…” pamphlets.

References

Casemine. Commonwealth v Neiman (2013)

https://www.casemine.com/judgement/us/5914fab5add7b049349a9a34

Collateral Consequences Resource Center. Commonwealth v Muniz (2017)

https://ccresourcecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Muniz-PA- Majority.pdf

Court Listener. Commonwealth v. Gomer WIlliams (2003)

https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/1518571/com-v-williams/

PA State Legislature Website.

https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/legis/li/uconsCheck.cfm?yr=2000&sessInd=0&act=18

The Unified Judicial System of Pennsylvania. T.L.P. v. PA State Police (2021)

https://www.pacourts.us/assets/opinions/Commonwealth/out/591md19_3-16-21.pdf

Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Walsh_Child_Protection_and_Safety_Act

![stuckIn1995_rally_header - PARSOL - Pennsylvania Assoc for Rational Sex Offense Laws (PA Megan's Law Resources) PARSOL Board Chair Josiah Krammes speaks at the PA Capitol Rotunda flanked by State Reps. Emily Kinkead and Tim Briggs (28 Oct 2025) [John Dawe/PARSOL]](https://parsol.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/stuckIn1995_rally_header.avif)